Halloween Special: Using a Ouija board to escape captivity

World War One: an incredible escape

Two individuals who exploited the power of the Ouija board - other than thousands of fake mediums - were Elias ‘Harry’ Jones and Cedric Hill.

In April 1916, ‘Harry’ Jones was a Welsh officer serving in the Indian Army Reserve. While fighting in Mesopotamia (an area which now largely comprises modern-day Iraq), Jones was taken captive at Kut-al-Amara by troops of the Ottoman Empire. With 13,000 other prisoners-of-war, he was force-marched 700 miles to a prison camp in Yozgad, Turkey. Five thousand POWs died along the way.

At Yozgad, Jones became friends with Lieutenant Cedric Hill, a pilot in the British Army’s fledgling Royal Flying Corps (RFC). An Australian by birth, Hill was brought up in Queensland. He went to school in Brisbane and, in 1911, while undertaking an apprenticeship with an engineering firm there, he saw Swedish American magician Nate Leipzig perform at the Empire Theatre. Seeing Leipzig perform prompted Hill to take up amateur conjuring. Post-war, he joined The Magic Circle, a British society for magicians.

For his primary career, Hill trained to install, run, and maintain industrial sheep shearing machinery. He was doing this when World War One started. Wanting he serve his mother-country, Hill left Australia to join the RFC. Two years later, while on a reconnaissance mission, his BE2c biplane was hit by enemy bullets. Forced to land, Hill was captured by Turkish troops and ended up in Yozgad with Jones.

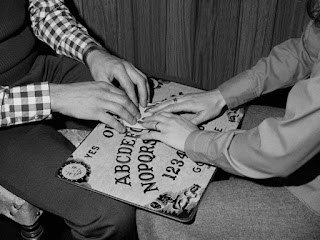

In February 1917, after almost a year in captivity, and with no end to the war in sight, Jones and Hill hit upon the idea of making a Ouija board to keep themselves and others entertained.

Jones showed a natural skill for manipulating his fellow inmates as a fake medium, and Hill ably fulfilled the role of his assistant. The pair performed seances, ran ghost-guided treasure hunts, and engaged in other occult-related fakery. Behind the scenes they used stage magic techniques, including sleight-of-hand and a two-person code-based mindreading act, to convince the other Allied prisoners that they could communicate with the spirit world.

Miraculously, Jones and Hill’s deception and subterfuge also hood-winked their Turkish captors. The camp commandant was persuaded they were communicating with a spirit guide who could lead him to find a stash of gold hidden outside the camp.

Eventually, the consummate conmen persuaded the commandant to transfer them to a Constantinople hospital for the mentally ill. Lieutenants Jones and Hill played their roles as ‘lunatics’ so successfully, they fooled the doctors and were returned to England in a prisoner exchange. Gallingly, after such a cunning escape effort, they arrived home only a fortnight before the Armistice.

E. H. Jones’ account of the escape, The Road to En-dor, was published in 1919. It became a classic World War One escape story and is still in print. In later life, Hill also wrote up the story, in a book called The Spook and the Commandant.

Fast forward to World War Two...

‘Harry’ Jones was now the registrar of the University College of North Wales until his death in 1942. Hill was still serving in the RAF, as a senior commander based in the UK.

But, on the other side of the world, in the jungles and paddy fields of South-East Asia, their famous Ouija board escape was about to be repeated.

When the Japanese army overran vast areas of Southeast Asia during World War Two, they took almost 200,000 Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen captive. Thousands more died resisting the invasion. Needing to prepare for an invasion from Burma into British India, the Japanese forced Allied POWs to build the Thai-Burma railway and other infrastructure. The work was crippling and the conditions brutal. Many thousands of POWs and Asian labourers died because of this treatment.

One of the enslaved POWs was Alexander ‘Con’ Findlay Anderson, a company quartermaster sergeant with the Federated Malay States Volunteer Forces. He found himself held in Chungkai, a work camp (and later convalescent camp) in Thailand.

In early spring 1943, 35-year-old Anderson used a scrounged oak headboard from a bed to make a Ouija board. He expertly decorated it with all the markings of the zodiac, letters, dates, and other artistic figures. He didn't believe in spiritualism but saw instead an opportunity to get the better of the camp guards and, possibly, to recreate Jones and Hill’s escape.

“The carving had all been done with just a piece of wire and a penknife. Once completed, he had used what was left of a tin of Cherry Blossom boot polish and the sap from the Tualang trees, which brought out a very highly polished Ouija board. In the centre of the board and turned upside down he placed an empty Bovril bottle on which were painted Biblical signs,” recalled Arthur Lane, a British POW.

Along with several colleagues, Anderson used the Ouija board to conduct fake seances for fellow POWs held at Chungkai camp. Typically, their readings would give positive answers to questions such as “when will the war end?” These boosted the POWs’ morale. Over time, the large gatherings in and outside the hut soon came to the attention of the POWs’ Korean guards.

The guards became absorbed by the Ouija board and the apparent ability of the POWs to communicate with the spirit world. One day, two guards joined in and asked their own questions of Anderson and his ‘spirit guides.’

Having hooked in the guards, Anderson and his team put in place the next stage of their plan. Over several sessions, they convinced the guards that there was treasure buried near to the camp. Eventually, the guards took the POWs off railway construction duties and gave them the task of gathering wood for fuel. This allowed them to ‘help’ the guards search for the treasure (and also to hide the treasure for the guards to find on a later trip).

The convincer for the buried treasure was a small canvas satchel containing several items of jewellery, gold rings, brooches, medallions and coins which the POWs had gathered from their own possessions, or fakes they’d made (some stamped with ‘authentic’ British hallmarks).

When the guards found the treasure, they sold it on to a trader in Kanchanaburi. They kept seventy-five per cent of the proceeds and gave the POWs twenty-five per cent "to keep the spirits happy". The money handed over to the POWs, 500 Bhat, was a significant sum for a bunch of starving prisoners.

The next stage of Anderson's plan - to convince the guards to help the POWs escape Chungkai - was potentially scuppered when the authorities sent the POWs to SongKurai, further up the railway. This ended the relationship the POWs had developed with the two guards at Chungkai. It looked like Anderson would need to restart the enterprise, with new guards, at SongKurai. On the flip side, their new camp was closer to Burma, which Allied forces were attacking. If the POWs could escape from SongKurai, there was a chance they could make it to friendly lines.

Two years later, in early summer 1945, Arthur Lane was working at Thanbazayat camp. This was at the end of the railway, just inside the Burma border. With a party of twenty men, the camp guards ordered Lane to clear an area of overgrown jungle to build new accommodation.

Just outside this area, Lane spotted a rectangular piece of hardwood dangling on a wooden stave. Carved onto the board were the names of those men buried below it. The board read:

“Here lie the remains of 3529270 Pte T. Jackson Manch Reg. CQMS C. Anderson FMSVF, A. S. H. Justice USS Houston. 33271… Pte Mar…”

The rest of the letters had been eaten away, except for some still discernible at the bottom of the board, which said, “Executed 1/11/43.”

On the reverse on the board, immaculately carved, were the remains of what had once been a Ouija board, the one Lane had last seen in Chungkai base camp. Near the board, Lane also found the remnants of a small cloth bag containing one or two bits of tarnished jewellery.

Post-war investigations revealed that Anderson and his ‘spirit guides,’ who’d been moved on from SongKurai to Thanbazayat, were executed by the Japanese authorities for attempting to escape.

Their plan to repeat Hill and Jones’ occult-inspired magic-fuelled escape failed, costing them their lives.

Today, they are buried in the Thanbazayat War Cemetery in Myanmar (formerly Burma).

Comments

Post a Comment