Sydney Piddington: telepathy in a Japanese POW camp (Part 1)

Australian’s Sydney and Lesley

Piddington were one of the most famous mentalism acts of all time.

They claimed to communicate telepathically and perform other feats of mental

ability. Popular performers in the UK, Australia and around the world, their act

was a radio and television sensation in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

“You are the judge!” was their

moniker, calling on their audiences to decide for themselves if telepathy was

real or not.

Incredibly, the origins of

their act were developed during World War Two, in a prisoner-of-war camp in

Singapore.

Learning magic

Born in Sydney near the end of

World War One, Sydney George Piddington (14 May 1918 – 29 January 1991) trained

and worked as an audit clerk after finishing school in 1934.

Alongside his day job ‘Sid’ or ‘Syd’ Piddington became interested in magic.

As a teenager, he joined a local magic society called the Independent

Magical Performers of Sydney (known as the ‘IMPS’). Their youngest member at the time, his specialities were card tricks, cigarettes, the linking rings, the pea-and-thimble distraction and whistling.

Despite suffering from a severe stutter, he performed frequently.

One of the earliest records of Piddington performing magic was 30 June 1935, age 17, during an IPMS Ladies Night. He entertained the ladies and other guests, which included world famous magician and illusionist Dante (Harry August Jansen). A high pressure gig for a young amateur magician just starting out.

Shortly after, he performed in ‘The Fooleries of 1935’, a show put on by the IMPS at St. James Hall, Sydney (and which broke the hall’s house records).

Piddington was elected as an officer of the IMPS society in September 1935, taking on miscellaneous responsibilities, such as sending club news to magic periodicals like USA-based The Sphinx. He also wrote occasional letters to local newspapers, evidently showing a early penchant for publicity.

At Christmas 1935/36, he performed in a charity show at Sydney’s Savoy Theatre, where he did his ‘Up in Smoke’ cigarette routine. The routine included ‘the disappearing lighted cigarette’. Unfortunately, it failed to disappear at one rehearsal, in his bedroom, and the fire brigade had to be called.

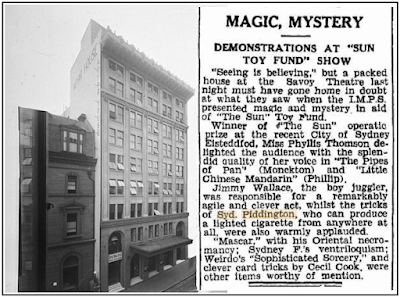

The Savoy Theatre in Sydney, Australia and an accompanying newspaper report mentioning Syd Piddington

(Source: Public domain / The Daily Telegraph, Sydney)

In a show for the Royal Automobile Club of Australia on 28 July 1936, he was billed as ‘Young Piddington: Australia’s Youngest Conjurer’.

A programme from Sydney Piddington’s performance for Royal Automobile Club of Australia (28 July 1936)

(Source: Royal Automobile Club of Australia)

In August 1936, Piddington was back at St. James Hall for another public revue put on by the Imps. A reviewer said, “Syd Piddington presented the cards to pocket in a routine which included the diminishing cards. The last cards taken from his pocket were Jumbo cards. He did a trick with a candle tube, blending it with a novel silk effect using a Jap production box.”

He performed in the ‘Hocus Pocus’ show back at the Savoy Theatre on 9 September 1936, where “his cigarettes [routine] were certainly no drawback to the show.”

Later, in a Christmas show, probably in the same year, he appeared as ‘Illusionist: Mr Sid Piddington.’ (He shared the bill with dancers, a comedian, singers and, oddly, a ‘Giant with Pony.’)

Standard magic was his intense passion –

until discovering The Jinx (a magazine for magicians specialising in

mental magic). He corresponded with the editor, Ted Annemann, and developed an

interest in ‘mentalism’.

All in all, Sydney Piddington appears to have been a fairly competent magician by his late teens. When he later reinvented himself as ‘demonstrator of thought transference’ after World War Two, his early foray into magic was played down as a passing schoolboy interest; presumably to distance his telepathy experiements from claims of trickery.

Off to war

Piddington was 21-years old when

his nation entered World War Two on 3 September 1939.

Answering the call to fight for

his country, Piddington enlisted for service in the Australian Army on 8 January 1940. He was called up for full-time duty on 20 January 1940 and, after basic training, served in a coastal defence artillery unit (127th Battery, 5th Heavy Brigade) in Australia.

Sydney Piddington, early 1940s, wearing Australian Army uniform

(Source: Unknown)

In May 1941, he transferred to a field artillery regiment (2/15th

Field Regiment) in the Australian Imperial Force (or AIF, which was the part of the army which deployed overseas).

He met fellow Australian Russell

Braddon in the 2/15th Field Regiment, and they became close friends.

Three months later, in August

1941, Gunner Piddington found himself alongside Braddon, deployed in British Malaya to

defend the colony against a possible Japanese invasion.

As the war progressed, their

artillery battery, equipped with Ordnance QF 25-pounders, was attached to the

45th Indian Brigade, stationed on the west coast of Malaya in Muar town (also

known as Banda Maharani). The brigade was tasked with blocking Japanese forces

seeking to cross the Muar River.

The Japanese attack on Malaya began

on 8 December 1941, when they launched an amphibious assault on the northern

coast of Malaya. Over the next five weeks, they advanced southwards towards

Singapore.

In one of the bloodiest battles

of the Malaya campaign, the Japanese overran the 45th Indian Brigade in a

battle which started on 15 January 1942. The attack forced the brigade to conduct

a fighting retreat towards Singapore.

The retreating Allies became

surrounded near the bridge at Parit Sulong, 20 miles south-east of Maur.

Piddington, Braddon and the rest of their colleagues in the 45th Indian Brigade

and the Australian 8th Division fought the larger Japanese forces for two days

until they ran low on ammunition, food and other supplies.

Eventually, able-bodied soldiers

were given the order, “Every man for himself; abandon positions; choose your

own route; make [for] any British force you can.”

Those who were too seriously

injured to move, surrendered. The Japanese brutally murdered many of these men,

in the Parit Sulong Massacre.

Sydney’s Piddington’s attestation form, completed when he joined the regular Australian Army

(Source: The National Archives of Australia)

Evading the enemy

and capture

Groups of five or six men, with

near no supplies, headed off into the jungle to escape the advancing Japanese

troops, “to claw one’s way through vicious vines, to evade the stinging

leaves, to scale sudden cliffs, to wade through endless swamps and brush off

the indefatigable leeches.”

Piddington (who was promoted to the rank of Acting Bombardier on 24 January) and Braddon travelled

in the same group, headed south towards Yong Peng and hoping to reach it before

it fell to Japanese hands. It was a torturous journey.

Sydney made it to the British-held

town just before the Japanese took it. But Russell Braddon, who got

separated from Piddington, was a few hours too late. While the British took

Sydney to Singapore, Braddon was captured by the Japanese. They took him to

Pudu Jail, a prisoner-of-war camp in Kuala Lumpur. Piddington and Braddon

didn’t meet again for nine months.

Back in Singapore, the army put

Piddington to work as a gun sergeant with another artillery battery (promoting him again, to Lance Sergeant, on 14 February). He was based on the

north-west tip of the island supporting attempts to halt any

attempt by the Japanese to cross from the Malay peninsula to Singapore island.

The sheer mass of the Japanese

forces outmatched the British-led defenders and on 8 February 1942, the

Japanese swept across the Jahor Straits. The battle for Singapore lasted

another seven days.

Piddington survived and avoided

capture until the fateful day of 15 February. Unlike his previous escape, this

time Piddington – and tens of thousands of other Allied soldiers – was ordered

to surrender by the British authorities. British Singapore, a jewel in the

Empire – had fallen to the Japanese.

Sergeant Sydney Piddington was

now a prisoner-of-war.

To learn how Piddington

rekindled his interest in magic as a POW and the role he played in operating a

secret radio, read Part 2 of this blog article here.

To read the other blogs in

this four-part article on The Piddingtons, see the Magic at War blog index here.

Quoted text mainly drawn from ‘The

Piddingtons’ (1950) by Russell Braddon.

*** AVAILABLE NOW ***

The Colditz Conjurer tells the amazing true story of Flight Lieutenant Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker, Battle of Britain pilot and prisoner-of-war magician.

Written by the Magic at War team, The Colditz Conjurer is a remarkable tale of perseverance, courage and cunning in the face of adversity. It features over 55 original photographs and maps. 129 pages.

Comments

Post a Comment