Nivelli: A death camp magician (Part 1)

Europe’s Jewish population in the 1930s numbered nine million. By the time World War Two ended in 1945, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime had murdered six million European Jews. They reduced many to ashes in extermination camps built specifically for the annihilation of Jewish people. The Nazis referred to the murder of Jews as ‘The Final Solution to the Jewish Problem’. Today, we call this genocide The Holocaust.

Herbert Lewin, a German Jew and magician, was one of those persecuted by Nazi Germany and its collaborators.

The story of his journey through The Holocaust, and how he used magic to survive, is both shocking and incredible…

Growing up in pre-war Germany

Born on 9 September 1906 in Berlin, Germany, Lewin became an amateur magician as a teenager. He favoured manipulation and stage tricks.

Lewin grew up during difficult times. Germany fought and lost World War One during his childhood. And it experienced an unprecedented period of hyperinflation in the early 1920s as he turned to adulthood. Possibly, his father died during the war, leaving Lewin as the primary earner for the family.

Turning his hobby into a profession to earn a living, Lewin adopted the stage name Nivelli (a reversal and slight alteration of his surname) and became a prominent performer in the Berlin area. Ominously, one of the reasons he used a stage name was because, “it was not possible for me to appear in antisemitic Germany as Lewin.”

He appears to have done well for himself, acquiring some business interests. He was a member of the Berlin Stock Exchange in the early 1930s and its youngest member.

And he married a Jewish woman called Gerda Freund.

The political instability in Germany, exacerbated by the hyperinflation, led to the collapse of the post-war German government in 1933. Adolf Hitler’s Nazi government replaced the Weimar Republic. Once the Nazis came to power, they introduced legislation to deny Jews freedom and restrict their rights. Eventually, Jewish people were barred from all professional occupations, banned from marrying non-Jews and owning property, their citizenship and right to vote was removed, and Jewish children were prohibited from attending state schools. In short, the Nazis aimed to exclude Jews from German society.

Refuge in Czechoslovakia

Seeking an escape from this intolerable situation, 29-year-old Nivelli, his wife and mother fled Germany in October 1933, taking refuge in neighbouring Czechoslovakia.

Settling in Czechoslovakia’s capital city, Prague, Nivelli continued performing as a magician. He also operated a magic shop business, with several kiosks in Prague selling magic and in other Czech cities, such as Teplitz and Aussig. The business did so well, that he couldn’t manage it alone and brought his sister, Hettie, over from Germany to help manage it. When Hettie married, his husband ended up working for Nivelli too.

In 1935, Gerda gave birth to a son, which the couple named Peter.

But more danger was coming to Nivelli and the thousands of other Jews in Prague and wider Czechoslovakia. Nazi Germany began a military occupation of the country in 1938 with the German annexation of the Sudetenland; an act which was – eventually – accepted by the United Kingdom, France, and Italy under the Munich Agreement. The agreement didn’t stop German aggression. Nazi forces occupied more parts of Czechoslovakia, leading to the creation of the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in early 1939, and German control of all parts of the country by 1944.

After the German takeovers, Jews soon became subject to discriminatory laws and regulations, similar to those in place in Nazi Germany.

Having experienced the Nazi’s treatment of Jews in Germany, Nivelli could foresee this extending to Jews in Czechoslovakia. Thousands of others could too, but while many chose to leave the country, Nivelli stayed:

“We had to run towards disaster with our eyes open... It was always clear to me what threatened us, but I was powerless, as our little mother was already almost 70 and our little child too small to jump onto a coal train, as thousands of people had done, in order to get to the port of Gdingen via Poland and, from there, via Sweden to England to save themselves. Even as Hitler entered Prague [March 1939], it would still have been easy for individuals to intentionally jump onto the slow moving coal trains from the Czech coal region.”

His sister Hettie escaped in September 1938 and managed to get to safety in the United States of America. Once there, she sponsored the paperwork to get Nivelli and his family over. The application was supported by U.S. officials but the immigration quota had already hit its limit.

Theresienstadt Ghetto

In November 1941, Reinhard Heydrich, the German chief of the Reich Security Main Office and acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, ordered the creation of a ghetto in Theresienstadt [Czech: Terezín], a former garrison town north of Prague.

Nivelli was selected, along with 342 other young Jewish men to prepare the town for the arrival of thousands of other Jews. Separated from his family, he was deported to Theresienstadt on 24 November 1941 and allocated to the Aufbaukommando [German: work detail]. Along with a trainload of 1,000 other men who arrived on 4 December, Nivelli was tasked with evacuating the existing non-Jewish Czech residents and then improving the ghetto’s infrastructure to accommodate a massive increase in people.

Gradually, Czechoslovakia’s Jewish population were arrested and sent to Theresienstadt. Housing approximately 40,000 people at a time (but peaking at almost 60,000), the ghetto served as a way-station to camps outside of Czechoslovakia. By the end of 1941, 7,400 people had been deported to Theresienstadt. Onward transports to Eastern Europe began in January 1942.

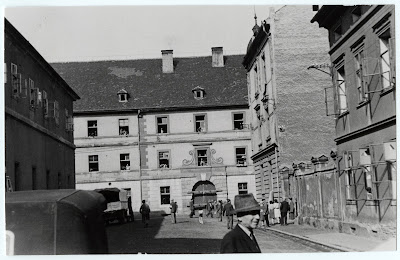

A street in Theresienstadt Ghetto during WW2

(Source ICRC)

In late May 1942, Czech resistance fighters gunned down Heydrich. Reprisals to this saw about 5,000 Jews killed, mainly in Prague. A further 13,000 people were arrested, including (research indicates) Nivelli’s wife, son and mother. They were deported to Theresienstadt and reunited with him there.

Used as propaganda by the Nazis (see “The Fuhrer gives the Jews a town” film), the ghetto was known for its relatively rich cultural life, despite its overcrowding and depravation. Activities (which were ramped up during infrequent Red Cross inspections) included concerts, lectures, and clandestine education for children. The inmates especially appreciated cabarets presenting material from the ‘good old’ days for the guaranteed nostalgia they created. It is almost certain that Nivelli contributed to this cultural life and these cabarets by performing magic for his fellow captives.

Nazi propaganda film “The Fuhrer gives the Jews a town” about Theresienstadt

(Source: Periscope Film II, public domain)

In reality, the conditions in Theresienstadt were appalling. Thousands of Jewish men, women and children were concentrated together and the poor conditions hastened the death of its prisoners from malnutrition and disease. “Within a short time, Vermin disease, skin typhus, child paralysis and famine moved in.”

Over 88,000 people were held at Theresienstadt for months or years before being deported to extermination camps and other killing sites. Three-quarters of the Jews who transited through the Theresienstadt did not survive the war, many dying in the ghetto itself.

While Nivelli was unfortunate to have been one of the first to be sent to Theresienstadt, this turned out to be beneficial, as the Aufbaukommando were exempt from deportation until late 1943. Therefore, for two years, he and his family were able to make life somewhat bearable in the ghetto.

This changed on 18 December 1943, when Nivelli’s mother received a transport docket. She was to be sent to Auschwitz, where the Nazis had created a new town for the Jews; or so the Theresienstadt inmates were told.

Nivelli’s own deportation to the East was delayed into 1944, possibly because he was seriously ill in the ghetto’s hospital:

“A doctor had given me an injection from a dirty needle for a heavy cold and I got blood poisoning on the right thigh, which was operated upon and chained me to the bed for 4 months.”

But, eventually, Nivelli, Garda and Peter received their transport dockets too.

Research shows that the German authorities moved the Nivelli family from Theresienstadt to a ‘family camp’ for Czech Jews in Auschwitz II-Birkenau in May 1944.

“I was locked up in a cattle box car with scores of others; all jammed up together like sardines in a can. No food, no water. And I landed in the horrible Auschwitz Camp.”

Auschwitz II-Birkenau concentration and extermination camp

Three hundred miles east of Theresienstadt, in Poland, Auschwitz II-Birkenau was a concentration and extermination camp. It was one of over 40 camps within the wider Auschwitz complex. Construction of Auschwitz II-Birkenau began in October 1941. It grew to 174 barracks, with a capacity for 125,000 prisoners (based on just 1m2 per person). The camp was the main gas chamber and crematoria site for the Auschwitz site. These were operational from March 1942 and, by the time Nivelli arrived, the Nazis were gassing and burning an average of 1,000 bodies a day.

On arriving at Auschwitz by train, most Jews and other untermensch [Nazi term: sub-humans, such as Romani people and homosexuals] were subjected to a selection process by the camp’s administrators. Those arrivals who were the most physically fit were moved into the barracks or allocated to nearby labour camps. Others, especially the elderly and physically disabled, were normally sent directly to the gas chambers to be murdered. Of the 1.3 million people sent to Auschwitz (of which 960,000 were Jews), 1.1 million were murdered. The Nazis gassed nine in ten Jewish people on arrival.

“After train journeys lasting three days and three nights, people were beaten out of the wagons with sticks at the Auschwitz railway station, had soap and towels pressed into their hands on the pretext they went into the delousing station. In reality, gas bombs were thrown into the delousing station and the corpses were later burned in their thousands, so that the chimneys smoked day and night.”

Nivelli and his family were not subjected to selection on arrival at Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Instead, the camp staff allocated them to the Bllb section of the camp. This section was an oddity, as the Jews held there were kept alive rather than being immediately gassed. Historians believe the reason for the family camp was to support Nazi propaganda. For example, the camp staff ordered the captives to send letters to relatives in Theresienstadt, reassuring them that transportation to Auschwitz did not mean death.

There were 32 barracks in section BIIb, which was just 600 by 150 metres in size. Men, women and children were housed separately. The Nazis put adult males and females to work, while the children were educated in a children’s barracks block, seeing their parents only at night.

The threat of death was ever-present in BIIb. The gas chambers and crematoria were in sight of the section, only a few hundred metres away. Conditions were primitive and the morbidity rate (from malnutrition, disease, exhaustion, and pneumonia) was high, and higher still when factoring in beatings from brutal guards.

“There were only beatings with sticks; the food was bad and minimal. No human could withstand this life for longer than 4 weeks. In this way, it was the elderly that died. Every morning, the corpses were brought out of the stables, which served as so-called accommodation. With feet dangling out, gold teeth were broken out of mouths, for it was, of course, the only thing that people possessed besides their own flesh and blood.”

Sadly, Nivelli discovered that his own mother had died of pneumonia on 13 January 1944, a month after she’d arrived at the camp.

On 8-9 March 1944, two months prior to Nivelli’s arrival at Auschwitz with his family, 4,000 people in the family camp (a third to a half of the occupants) were liquidated: making space for the new arrivals from Theresienstadt. Section BIIb was a tenuous place to exist.

Somehow, Nivelli had survived a decade of persecution in Germany and in Czechoslovakia. He’d survived two years in Theresienstadt Ghetto. And he’d survived the transit to Auschwitz and avoided selection for immediate gassing on arrival. But could he survive section BIIb?

*****

Read the second and final part of this true story here.

Nivelli wasn’t the only magician held in Auschwitz. Others include Werner Reich, Miss Blanche and, probably, Dr Laszlo Rothbart. The Nazis murdered more Jewish magicians in other German concentration and extermination camps, including Dutchmen Louis Lam and Ben Ali Libi.

Some other articles about Nivelli refer to his original name as Herbert Levin, not Herbert Lewin. I have used the latter, as this is the form Nivelli used himself in the 1951 primary source reference above.

*** AVAILABLE NOW ***

The Colditz Conjurer tells the amazing true story of Flight Lieutenant Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker, Battle of Britain pilot and prisoner-of-war magician.

Written by the Magic at War team, The Colditz Conjurer is a remarkable tale of perseverance, courage and cunning in the face of adversity. It features over 55 original photographs and maps. 129 pages.

Comments

Post a Comment