Cortini: A prisoner of the Japanese

Dutch magician and illusionist The Great Cortini got caught up in the war in the Far East and ended up a prisoner-of-war of the Japanese. He used his magic skills to boost the morale of his fellow POWs and to survive the brutal and harsh conditions of captivity and hard labour.

Note: This blog was updated in October 2022 with additional information and images.

Prisoner of the Japanese

When the Japanese army overran vast areas of Southeast Asia and the Pacific during World War Two, they took almost 200,000 Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen captive. Thousands more died resisting the invasion.

The war in Europe had weakened the commitment of Britain, France, and The Netherlands to the region. The Far East was wide open to Japan's dream of dominance throughout Asia.

One of the captured servicemen was a Dutch entertainer known as The Great Cortini or Professor Cortini. Born on 29 December 1912, Cortini (real name Johan Hubert Crutzen) came from Vaals in the south-eastern corner of The Netherlands. A magician/illusionist by occupation, he served as a soldier (Private Second Class) in a transport division during the war.

Cortini was in Magelang, central Java, supporting the defence of the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) when the Japanese began a campaign to capture the islands on 17 December 1941. The invasion started ten days after the Japanese attack on the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, which led to The Netherlands declaring war on Imperial Japan.

(Source: Public domain)

As the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies went on, they captured thousands of Dutch military personnel and civilians. Java formally surrendered to the Japanese on 12 March 1942. On or around this data (probably the 17 March) and Cortini became a prisoner-of-war (POW).

Initially the Japanese held captured personnel on the islands where they were taken captive. So Cortini’s first eight months as a prisoner of war (POW) were spent in Java.

In late 1942 though, the Japanese transferred many of the Dutch POWs and civilian detainees from Java and Sumatra to Singapore, where most of the British, Australian, and other Allied prisoners were held.

Cortini was transported on a ship heavily crowded with other POWs (known as a hell ship due to the appalling conditions and numerous deaths in transit) from Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies [now Jakarta in Indonesia]. The SS Oryoku Maru left Batavia with POW No. 5 Group on 27 October 1942 and arrived in Singapore a week later, on 2 November.

SS Oryoku Maru, a Japanese passenger / troopship used to transport POWs

(Source: Wikipedia)

The POW’s destination, Singapore, had fallen to the Japanese in February 1942 when the British-led garrison there was forced to surrender. The Japanese detained some 3,000 civilians in Changi Prison in the eastern part of the island and converted a collection of nearby British Army’s barracks into a camp to hold 50,000 Allied POWs.

Changi concert parties

Cortini arrived on the Changi peninsula in early November 1942. By that time, the prisoners had set-up several concert parties to counter the boredom of captivity. Concert parties were groups of entertainers, some amateur and some professional, drawn from the ranks of the units held as POWs or the civilians held alongside them. They performed plays, musicals, variety shows, concerts and other entertainments to boost the morale of their audiences.

The first month Cortini arrived, he appeared in a variety show with the 18th Division Concert Party. The concert party was a group of ten performers, including British artilleryman and member of The Magic Circle, Fergus Anckorn. The POWs put the show on in The New Windmill Theatre, a stage/auditorium built in a former NAAFI building. Cortini, a newly arrived attraction, was the hit of the show:

“The Dutch illusionist, the ‘Professor’ Cortini, performed with us. He wasn’t, of course, a professor of anything. In fact, he was hardly educated at all, but he was a first-class illusionist.”

Naturally, as a professional magician, Cortini went on to take a leading role in forming a Dutch concert party.

“He called himself ‘the Great Cortini’ and his act was called ‘Cortini’s Magical Eye’. His troupe referred to him as ‘the Professor’ and when I went to see if I could meet him, I was told by his troupe, ‘The Professor is resting at the moment. You’ll have to come back later.’ Well, I did go back later and had a good chat with ‘the Professor’. He invited me to join his show as a conjurer...”

In January 1943, two months after their first performance together, the pair collaborated on a full show dedicated to magic. Magic Nights was performed in a space known as The Palladium Theatre in the Roberts Hospital area of the POW complex. Anckorn recalled:

“As the theatre’s facilities were so good, we’d put on full magic shows, with the Professor’s illusion act – sawing people in half and things like that – and me doing a limited amount of conjuring.”

“One show we did started in a macabre tone in keeping with our surroundings. The lights would go down and the curtains would be partially opened with the Professor standing there between them. But, as you looked, he would gradually turn into a skeleton – a complete skeleton – and then he’d turn back into a man again, bow and disappear behind the closing curtains.”

Other illusions included a guillotine, a suspension and possibly one involving live animals.

A programme for the Magic Nights, starring The Great Cortini with Fergus Anckorn (January 1943)

(Source: The Jack Wood Collection)

The list of acts in the Magic Nights show (January 1943)

(Source: The Jack Wood Collection)

Given that Cortini was a prisoner-of-war in a cramped, squalid POW camp, it is incredible that he first put on a full evening magic show, and second, that it featured seemingly high-quality illusions. I don’t know of any other examples of magic being performed at this scale during World War Two in any other POW camp.

Cortini may have kept hold of some small props when he got captured and during his captivity in Java and his transfer to Singapore, but must have made the rest while held in the Changi POW complex. Such was the scale of his show in Changi, he was supported by his own company manager, stage manager, electrician and assistants (drawn from his fellow POWs).

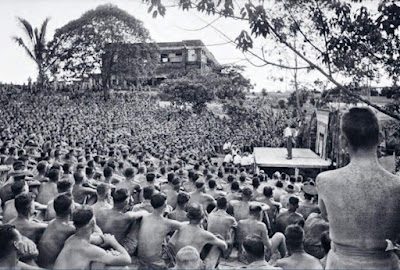

Allied POWs at Changi POW complex in eastern Singapore

(Source: Imperial War Museum)

After several months of crowding prisoners into the Changi Prison and the nearby (former) British Army barracks, the Japanese selected drafts of POWs to move out of the Changi peninsula to new camps in Thailand. Better conditions were promised by the Japanese. But the relocation was a journey to hell.

The Death Railway

To help their war effort, the Japanese decided to build a railway from Thailand to Burma. This would allow them to resupply their troops fighting the Allies in Burma by land, bypassing sea routes which were vulnerable to attacks from Allied warships and submarines. Once the railway was completed the Japanese planned to attack the British in India, and the Allied supplies to China.

Construction of the Thai-Burma railway (also known as the Burma–Thailand or Burma–Siam railway) began in mid-1942. It ran from Nong Pladuk in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma (now Myanmar). A momentous construction effort, it took over a year to complete, with the railway’s 258-mile route cutting through paddy fields, dense jungle, hills and crossing several rivers.

The Death Railway (Thai-Burma Railway)

(Source: Philip Cross)

To free up resources for other fronts, the Japanese military used 60,000 prisoners of war and detainees to build the railway. These included troops from the British Empire, Dutch and colonial personnel from the Netherlands East Indies and several hundred US troops captured mostly during the Battle of Java Sea. When this workforce proved incapable of meeting the tight deadlines set by the Japanese for finishing the railway, they enticed or coerced 200,000 Asian labourers or rōmusha into working for them.

Prisoners in the Changi peninsula were dispatched to live in work camps in either Burma or Thailand to build the railway. Cortini was transferred from Singapore to go ‘up country’ on 15 January 1943. It is believed that he was first sent to a camp at Nong Pladuk. Laying within paddy fields and banana plantations, Nong Pladuk was the starting point for the Thailand end of the Thai-Burma railway. But he may not have stayed there for long, as like many of the Dutch contingent of POWs, he ended up in Burma. He based at Regue, 100km from the end of the railway.

Far East POWs labouring on the Thai-Burma Railway

(Source: BBC)

Starved of food and medicines and forced to work impossibly long hours in remote unhealthy locations, over 14,000 POWs died building the Thai-Burma railway. The number of rōmusha dead probably reached up to 94,000.

The death rate among Dutch prisoners and detainees working on the railway was 16%.

Mental escape from forced labour

Escape from the POW camps in Thailand and Burma wasn’t a practical option. The bases were too far from friendly lines, the journey too hazardous, and the chances of survival too slim.

Seeking instead mental escape, some POWs found the energy to put on entertainments for their fellow prisoners in the evenings or on occasional rest days.

Working on camp entertainments gave those involved a focused goal and a sense of team spirit while they laboured on the railway. And when the POWs staged the play, revue, or concert, it brought a genuine sense of satisfaction. These things were difficult to foster in the harsh conditions faced by the Far East POWs. A second benefit was simple enjoyment and escapism. The performers and stage staff could become absorbed by the production from an early stage of rehearsal. During the performances, they and their audiences might escape for an hour or two into a happier world.

Charles Pryor, a sailor who survived the sinking of the USS Houston and ended up as one of the few hundred American POWs working on the railway, remembered seeing one of Cortini’s makeshift performances at Hlepauk on the fringes of the Burmese jungle:

“I think we worked six weeks before we had our first yasumi [Japanese: rest] day. I know when that first day came, well, some of the guys that had any talent put on a concert; we gathered on a bit of high ground out there and let that be the performing stage. Those that could do anything sang a song or recited a poem or something… We had a Dutchman with us who was a professional magician [Cortini]. Of course, he was a good entertainer… Some of the rōmusha in a neighboring work camp came over to watch the show, but when the magician performed a trick in which a handkerchief danced in the air, they made a hasty exit.”

Cortini’s magic skills helped him survive the harsh conditions of his captivity and forced labour. When his Japanese captors learned of his performing ability and the camp commandant often sent for the Dutchman to perform tricks. He earned himself a favoured, if perilous, position. Some guards were so impressed with Cortini’s magic effects that they bowed low when they saw him in respect, and occasionally allowed him out of the prison camp unattended.

A Japanese POW record card for Cortini (Johan Hubert Crutzen)

(Source: Netherlands Archives)

A flying concert party

In November 1943, a year after the first POWs from Singapore arrived to work on the Burma side of the railway – and a month after the railway was largely completed – the Japanese commandant there ordered that there would be a series of POW revue shows to mark the occasion. A group of prisoner-performers were drawn from various camps and formed together as a touring company, or a ‘flying concert party.’

Demanding the least amount of rehearsal time, variety shows or revues were the easiest productions for the POWs to put on. Held together by the jokes and running commentary of a compere, or a thin plot-line, they could incorporate the widest range of performers one might find in camp.

Cortini was called on to join this multinational concert party, where he performed alongside Brits, Australians, and others. With minimal preparation and rehearsal, the concert party gave their first performance on 19 November at the Aungganaung (105 kilo) work camp, before going on a hectic five-day tour.

The flying concert party shuttled up and down the line, performing in the POW work camps, most of which had no entertainment of their own. To prepare for the troupe’s visit, the Japanese ordered POWs in camps without stages to construct one.

After a year of working on the railway, the show was a welcome, albeit fleeting, relief for the POWs.

After the show at Little Nikki, just across the border in Thailand, Major Jim Jacobs with rail-laying Mobile Force No. 1 wrote about the concert party’s visit:

“They gave us a splendid show that evening… It was a professional, refreshing show that proved beyond doubt, no matter the suffering, there is always a group who can minimise miserable moments and build up morale.”

The three hundred Dutch/Indonesians who had walked over from the main camp at Little Nikki to hear the concert shared his opinion.

At Paya Thanzu Taung, POW Arnold Jordon said that:

“One of the finest displays of wizardry and sleight-of-hand one could wish to see anywhere was given by a clever young Dutch lad [Cortini] who, with no more than a tattered shirt to hide his wash-board ribs and to make do for voluminous sleeves etc. of the stock-in-trade, delighted us with his performance.”

Performing magic without props and secret gimmicks is incredibly difficult, but Cortini improvised and overcame these challenges. Examples of the tricks he performed included levitating iron bars and producing coins from blocks of wood.

On the flying concert party’s way to Khonkhan, the farthest camp west on their tour, the concert party stopped at Regue, Cortini’s home camp and several of the other Dutch/Indonesian performers on the tour. There they gave two performances before leaving for Khonkhan. They finished their tour at Mezali on 23 November, where three days later they gave a command performance for Lieutenant-Colonel Nagatomo.

Nagatomo suggested the concert party become permanent and continue to tour the railway camps. But the performers wanted no part of that scheme, as they considered it unfair to be entertaining permanently while their fellow POWs laboured. Two days after the command performance, the all-stars split up and returned to their home camps.

Moving on

A month later, in December 1943, Cortini performed in another show. The production, at Regue, was an elaborate Afscheidsvoorstelling (Dutch: farewell performance) put on by the Rimboe Club, which was one of the concert parties. Other acts on the bill included an opening ‘repertoire’ (comic patter?) by van Dorst (the Dutch unit’s adjutant); a mappentrommel (Dutch: grab bag of jokes) by van Dalmen “and his guys”; van Damm with his musicians, the “Dutch Blue Four”; and a finale featuring a ‘Miss Waikiki’ performing a Hawaiian hula.

Souvenir programme for the Afscheidsvoorstelling featuring Cortini (December 1943)

(Source: Lodewikus D. De Kroon, Museon, the Hague, Netherlands)

They put the show on in honour of a draft of POWs from Regue, leaving for a new base camp in Thailand. Cortini was sent to Thailand in a later draft. More hard labour followed.

There is also some evidence he may have been sent to French Indo-China [now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos] in late 1944 or 1945.

Victory over Japan

After that farewell performance at Regue, it was another 18 months before the Allies forced Imperial Japan to surrender, on 15 August 1945. With good fortune, and a little help from his magic, 32-year old Cortini survived Japanese captivity. He was severely malnourished and ill, but alive.

It is well documented that the entertainers among the POWs and civilian detainees, with their music, magic and mirth, were instrumental in helping the POWs on the Thai-Burma railway endure the unimaginable hardships of that construction project and the years of imprisonment that followed its completion.

The entertainment they produced would be, for many, the difference between living with hope and sinking into despair.

Aboard a transport ship sailing home following liberation, the value entertainment had played in the lives of the POWs was discussed by Medical Officers. “Many lives were saved,” they said. “Not only among those who were actually sick, but those who might easily have succumbed if they hadn’t had some reason for living.”

Post-war

Post-war, Cortini headed to The Netherlands to recuperate and return to his career in magic

Back in Amsterdam in his home country, Cortini attended an International Congress of Magicians in August 1946. The conference drew together 300 magicians from across Europe. Among the registrants were two other former Far East POWs, including Fergus Anckorn.

Article about Cortini attending the International Congress of Magicians

(Source: Dundee Evening Telegraph, Mon 12 Aug 1946)

The international congress led to the creation of the Fédération Internationale des Sociétés Magiques (FISM) (French: International Federation of Magic Societies) two years later, which still exists today.

As theatre work gave way to hotel and nightclub gigs in the 1950s, Cortini became a nightclub magician. He toured internationally and even returned to perform in Singapore.

A rare photograph of Cortini on an engagement in Calcutta, India (1960)

(Source: H.M. Vakil’s ‘Cigam’ Magazine, 1960)

He based himself in Amsterdam and opened a magic shop there in later life.

A link to Houdini?

As a POW, and perhaps pre-war and post-war, Cortini promoted himself as a supposed nephew of Hungarian-American magician and escapologist Harry Houdini. Fergus Anckorn dismissed this as a promotional ploy. But, take another look at Cortini's POW record card in this blog. It states that Cortini’s mother’s name was A.B. Houdini...

However, Cortini was highly unlikely to be related to Harry Houdini. The surname Houdini was a made-up stage name, formed by adding an ‘i’ to the name of a famous Nineteenth Century French magician called ‘Houdin.’ So no family members carried on the ‘Houdini’ surname, as their actual surname name was Weisz (or anglicised as Weiss). And Houdini only had one sister, who was born and lived in America, and she was called Carrie Gladys Weiss.

Source documents for this blog article include 'Captivity, Slavery and Survival as a Far East POW: The Conjuror on the Kwai' by Peter Fyans. Also see, 'Captive Audiences / Captive Performers: Music and theatre as strategies for survival on the Thailand-Burma Railway 1942-1945' by Sears A. Eldredge. Both are highly recommended.

Look out in this blog for upcoming articles about Fergus Anckorn and Sydney Piddington, two other Far East POW magicians.

Professor Cortini should not be confused with Cortini (1890-1954), otherwise known as Paul Korth, who was a German magician.

With grateful thanks to Glenda Godfrey for her kind assistance in helping with the research for this article.

Related article: ‘Fred Kolb: First Allied magician in occupied Japan?’ Blog link.

Related article: ‘Magic Marine awarded U.S. Medal of Honor.’ Blog link.

Related article: ‘Magician leads E.N.S.A. company through firefight with Japanese troops... and survives!' Blog link.

Research supported by The Good Magic Award from The Good Thinking Society

*** AVAILABLE NOW ***

The Colditz Conjurer tells the amazing true story of Flight Lieutenant Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker, Battle of Britain pilot and prisoner-of-war magician.

Written by the Magic at War team, The Colditz Conjurer is a remarkable tale of perseverance, courage and cunning in the face of adversity. It features over 55 original photographs and maps. 126 pages.

$15,00

0

Ferrari"

Comments

Post a Comment