Fergus Anckorn: The Conjurer on the Kwai (Part 1)

The first of four blogs telling the incredible wartime experiences of Fergus Anckorn, an amateur magician who used magic to survive captivity and slavery as a POW in the Far East during World War Two.

Learning magic

Born in late 1918, at the close of World War One, Fergus Anckorn started learning magic from an early age. He performed his first paid show aged seven. As a teenager, he befriended magician Major Lionel Branson, a major in the Indian Army who lived nearby. When Branson became vice-president of The Magic Circle (a British-based magic society), he encouraged Anckorn to join, which he did in 1937. At age 18, Anckorn became the youngest member of The Magic Circle (and years later became its oldest practising member).

Becoming a magician-soldier

When war was declared in 1939, the authorities conscripted 21-year-old Anckorn into the British Army. After completing recruit and specialist training, he was assigned to the 118th Field Regiment Royal Artillery. The 118th was tasked with defending the UK from an invasion by Nazi Germany. After several months with his regiment, Anckorn was offered the opportunity for a special role as an entertainer-in-uniform.

After a successful audition, he joined the 18th Infantry Division Concert Party, called The Optimists (a name inspired by a professional civilian concert party which performed during the inter-war years). A concert party in the military context was a group of soldiers, sailors or airmen who were amateur or professional entertainers. Exempt from normal soldiering duties, the entertainers toured units in the division, bringing entertainment to bored troops living away from home.

The Optimists consisted of two pianists, a violinist, an accordionist, two singers, an actor, and an impersonator, with Anckorn as the magician. He described his experience with the troupe in post-war interviews:

“The shows were made up of all kinds of sketches, plays and general buffoonery, with all of us contributing ideas and performing them whilst those of us with speciality skills would also have our own spot. Mine, of course, was conjuring tricks.

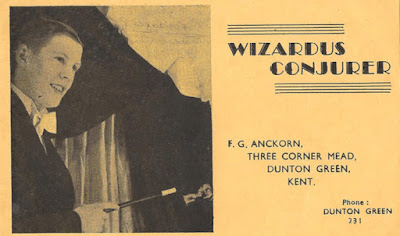

“My stage presence as Wizardus was established by my being dressed in white tie and tails, no matter where the show was held… I would always do two sets in the show. The first would be silent and done completely to the music that George would create. Typically, in this set, I would walk on producing lit cigarettes out of thin air and then vanish them again, after drawing on each to prove it was real. Then I might do various tricks with a piece of rope – cutting it and putting it back together again, or making it extend and so on. Then I might do the billiard balls trick, producing first one, then two, then three, then four billiard balls between my upheld fingers and vanishing them again. Various playing card flourishes would also come into the act as well as tricks with coloured silk handkerchiefs. In the second half of the show, my set would involve the audience and I would do predictions and memory challenges.

The Optimists toured the brigades and regiments within the 18th Infantry Division and travelled with them as they moved from East Anglia, to Scotland and down to the Midlands at the backend of 1940 and into 1941.

“The great thing for me was that I was doing my magic every night. In the end, I could do it at the drop of a hat in any situation – nothing fazed me. The funny thing was that I’d always been a shy person but every time I got on stage, I didn’t care how many people there were in the audience or what their status was – I just became extremely confident. What’s more, the concert party seemed to be going on for such a long time that we all began to think we’d for doing it for the rest of the war.”

Off to the Far East

After almost a year as a soldier-entertainer, Anckorn returned to anti-invasion duties in late spring 1941. In autumn the same year, his unit was sent to the Far East as part of the 55th Brigade. Two days before they sailed, Gunner Anckorn’s commanding officer summoned him and asked if he’d packed any magic tricks. He hadn’t, so the commanding officer gave Anckorn £30 and ordered him to buy some props. Anckorn placed an order by phone to Davenports’ magic shop in London. Incredibly fast, the package arrived in Liverpool the next day, just before the convoy sailed.

Anckorn left the Port of Liverpool in late October 1941 and headed for the Far East. By the time his unit arrived in Singapore in early February 1942, Japan had joined the war (following its attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941).

As Anckorn disembarked in Singapore, there was the sound of bombing and destruction all around. Since 8 December 1941 (the day after the Pearl Harbour attack), the Japanese had advanced with 30,000 men down the Malayan Peninsula to outflank the British garrison. They were bombarding the island with artillery and aircraft attacks and getting ready for an invasion. A few days after Anckorn’s arrival, on 8 February, the Japanese attacked the weakest part of the island and established a bridgehead.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered military commanders to fight to the last man and to die with their troops, such was the importance of Singapore as the foremost British military base in South-East Asia. “The honour of the British Empire and the British Army is at stake,” he said.

The Fall of Singapore

Anckorn took part in the defence of Singapore, fighting with his unit which provided artillery support to the infantry and other military forces. At the height of the battle, on 13 February, his vehicle was caught in a Japanese bombardment and hit by an anti-personnel bomb. As the vehicle lurched onto its side, Anckorn realised he was wounded.

“I moved to open my door and get out but found my right hand hanging off. There was no pain, but it was completely unresponsive and I could see that something had gone through my arm as well and opened an artery. Blood was everywhere.”

Such were Anckorn’s injuries that his colleagues initially left him for dead. Sometime later, they recovered and evacuated him to Alexandra Military Hospital. Apparently, a surgeon treating Anckorn was planning to cut off his hand until someone called out, “You can’t cut his hand off, Sir. He’s a conjurer!” The surgeon managed to save the hand.

Fergus Anckorn explains how he got wounded and what happened during the Japanese attack on the British military hospital in Singapore (audio clip)

(Source: YouTube)

But Anckorn was far from safe. As he lay in his hospital bed, drifting in and out of consciousness, the Japanese attacked the hospital (in retaliation against retreating Allied soldiers who’d fired at them from the hospital grounds). The Japanese killed an estimated 50 staff and patients on 14 February, bayoneting many of them as they lay in bed or on the operating table. The next day they returned and killed another 150.

Miraculously, Anckorn survived the attack on the hospital, probably, he thought, because there was already so much blood on his bed that the Japanese assumed he was already dead.

When he next woke up, Anckorn was lying on the floor of the Chinese High School on the island. “Where are we?” he asked. “We’re in the bag,” came the reply from a fellow soldier. It was 15 February. Singapore had fallen.

About 80,000 British, Indian, Australian and local troops became prisoners of war when the Japanese captured the island, joining 50,000 taken in Malaya. Churchill called it the worst disaster in British military history.

Lieutenant-General Percival, Commander Malaya Command and his party carry the Union flag on their way to surrender Singapore to the Japanese on 15 February, 1942.

(Source: Public domain)

For further information on Fergus Anckorn’s life in magic and wartime experiences, read Captivity, Slavery and Survival as a Far East POW: The Conjuror on the Kwai by Peter Fyans and Surviving by Magic by Monty Parkin. Also see, Captive Audiences / Captive Performers: Music and theatre as strategies for survival on the Thailand-Burma Railway 1942-1945 by Sears A. Eldredge.

Read Part 2 and Part 3 of this article and look out for Part 4 to find out what happened after Anckorn was captured by the Japanese and how he used magic to survive captivity.

*** AVAILABLE NOW ***

The Colditz Conjurer tells the amazing true story of Flight Lieutenant Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker, Battle of Britain pilot and prisoner-of-war magician.

Written by the Magic at War team, The Colditz Conjurer is a remarkable tale of perseverance, courage and cunning in the face of adversity. It features over 55 original photographs and maps. 126 pages.

Comments

Post a Comment