Fergus Anckorn: The Conjurer on the Kwai (Part 2)

The second of four blogs telling the incredible wartime experiences of Fergus Anckorn, an amateur magician who used magic to survive captivity and slavery as a POW in the Far East during World War Two.

Captured and recovery

On 13 February 1942, during the Battle for Singapore, a Japanese attack injured magician-soldier Fergus Anckorn. The British garrison surrendered two days later, causing Anckorn to become a prisoner-of-war (POW).

Anckorn spent his first three months as a POW as a patient in the RAF Hospital at Changi in eastern Singapore. The medical facility was next to Kitchener Barracks, Roberts Barracks, and Selarang Barracks. The British built the military base at Changi to accommodate forces defending the island. After the Fall of Singapore, the Japanese turned the Changi complex into a POW camp.

Fergus Anckorn performing a card fan display (pre-war)

(Source: Fergus Anckorn)

While recuperating, Anckorn learned to compensate for his shattered left knee by using a homemade pulley contraption. He taught himself to do card tricks with his damaged left hand: a self-directed form of physiotherapy. The doctors discharged him from the hospital in May 1942.

After the shock of capture had worn off, the POWs at Changi adjusted to life in captivity and organised themselves to survive as best that they could, under supervision by the Japanese military authorities. As boredom set in, they organised entertainments, such as variety shows, plays, music recitals, etc.

Changi magic

Among the tens of thousands of POWs crammed into Changi, Anckorn met up with the remaining members of his former concert party, The Optimists. Unfortunately, this disbanded before Anckorn could contribute to any shows being put on.

But the 18th Division (who Anckorn served with before he became a POW) formed ‘The New Windmill Players,’ an amateur dramatics group that presented plays on a renovated stage in the ballroom of the former NAAFI [recreational centre] renamed the New Windmill Theatre. Anckorn performed in their Windmill Variety No. 1 show in late August and early September.

An observer of one of Anckorn’s performance recalled:

“A tall, fair young man dressed in full evening dress with white tie and tails (where did he get his clothes?) was very clever with a pack of cards and he entertained and mystified the audience with various tricks.”

The Selarang Incident interrupted the performances. On 2 September 1942, the Japanese ordered all the POWs in Changi to assemble on the parade ground of the Selarang Barracks. The Japanese administration demanded that every POW sign a form swearing he would not attempt to escape. They rounded up some 17,000 POWs on the parade square and threated to shoot all those who didn’t comply. A stand-off ensued as, en masse, the Allied POWs refused to sign. The situation lasted two days until the Japanese and POW leaders reached a compromise.

Selarang Barracks, Changi, Singapore during the Selarang Incident in early September 1942

(Source: Public domain)

After this incident, Anckorn and the other POWs returned to their barracks, and camp entertainment restarted.

New arrivals

In mid-September 1942, the arrival of the first substantial party of POWs from camps in the Netherlands East Indies altered prison life at Changi. These ‘Ex-Java Parties’ (as they came to be known) contained Australian, British, Netherlands East Indies, and American soldiers, as well as airmen and sailors. The Japanese also moved POWs held in Malaya to Changi. There was an acute shortage of accommodation, food, and medical supplies for all the POWs, now 50,000 of them, making life at Changi difficult and uncomfortable.

Among the new arrivals was a Dutch-Indonesian magician and illusionist called The Great Cortini. Cortini started performing in the Dutch camp at Changi and Anckorn met up with him there. Cortini invited Anckorn to join his show. But Anckorn’s support act was short-lived, as his injured hand limited his ability to perform.

However, the two magicians performed together in an 18th Division variety show at the New Windmill Theatre in November 1942. And in a full-evening magic show called Magic Nights at The Palladium Theatre in the Roberts Hospital area of the camp in January 1943.

A programme for the Magic Nights, starring The Great Cortini and Fergus Anckorn

(Source: Glenda Godfrey)

Meanwhile, it became apparent that the Japanese were using the Changi peninsula as a mass transit camp. For, as POWs were being brought to the camp, others were being moved out. The Japanese despatched drafts of men from Changi to ‘Up Country’ locations in Burma and Thailand. The captors offered the POWs better conditions, away from the squalor of Changi. But the relocations were a journey to hell.

The Death Railway

To help their war effort, the Japanese decided to build a railway from Thailand to Burma. This would allow them to resupply their troops fighting the Allies in Burma by land, bypassing sea routes which were vulnerable to attacks from Allied warships and submarines. Once the railway was completed, the Japanese planned to attack the British in India and the Allied supplies to China.

Construction of the Thai-Burma railway (also known as the Burma–Thailand or Burma–Siam railway) began in June 1942. It ran from Nong Pladuk in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma (now Myanmar). A momentous construction effort, it took over a year to complete, with the railway’s 258-mile route cutting through paddy fields, dense jungle, hills and crossing several rivers.

To free up resources for other fronts, the Japanese military used 60,000 Allied prisoners of war and detainees to build the railway. These included troops from the British Empire, Dutch and colonial personnel from the Netherlands East Indies and several hundred US troops captured mostly during the Battle of Java Sea. They also enticed or coerced 200,000 rōmusha (Asian labourers) into working for them.

The Japanese authorities sent prisoners in Changi to live in work camps in either Burma or Thailand to build the railway.

The Death Railway (Thai-Burma Railway)

(Source: Philip Cross)

Kanburi and the ‘Bridge over the River Kwai’

In November 1942, it was Anckorn’s turn to head ‘up country,’ He ended up at a camp in Kanchanaburi, known by POWs as Kanburi, near a settlement called Tamarkan in Thailand. There, he was put to work on building the so-called ‘Bridge over the River Kwai.’ The 1957 film with that name was historically inaccurate in many ways. In reality, there were two bridges, a wooden service bridge and a permanent concrete/steel one. And neither of them was actually on the Khwae (or Kwai) Noi River. They were a short distance away, on the Mae Khlaung River, near to where it joined the the Khwae Noi River. Anckorn worked first on the wooden bridge, and then later on the wooden/steel one.

Wang Pho - a new challenge

After he worked on the bridges, the Japanese sent Anckorn deeper into the jungle to Wampo Central/113 Kilo in Wang Pho. This was one of three camps, 70 miles from the start of the railway, housing POWs charged with constructing a section of the line in hilly jungle terrain alongside the Khwae Noi River. Part of the task involved blasting and chiselling the cliff faces above the river to create the space needed for the railway. Then building a long wooden viaduct on top of which the railway would run. This was a much tougher assignment.

Watch a video of the completed Wampoo Viaduct here.

It was a tough section of the Thailand-Burma Railway to build and took almost 2,000 POWs and rōmusha seven months to complete.

Mental escape from forced labour

Escape from the POW camps in Thailand and Burma wasn’t a practical option. The bases were too far from friendly lines, the journey too hazardous, and the chances of survival too slim. Most of the Far East POWs were severely malnourished, near to exhaustion, and lacked the physical or mental energy to attempt to escape. Plus, Anckorn’s leg injury limited his ability to complete his daily duties, let alone trek miles through the jungle to safety.

Seeking instead mental escape, some POWs found the energy to put on entertainments for their fellow prisoners in the evenings or on occasional rest days.

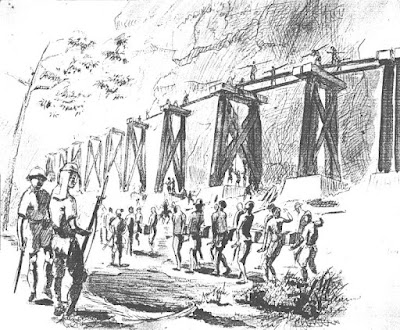

Far East POWs labouring on the Thai-Burma Railway

(Source: BBC)

Working on camp entertainments gave those involved a focused goal and a sense of team spirit while they laboured on the railway. And when the POWs staged the play, revue, or concert, it brought a genuine sense of satisfaction. These things were difficult to foster in the harsh conditions faced by the Far East POWs. A second benefit was simple enjoyment and escapism. The performers and stage staff could become absorbed by the production from an early stage of rehearsal. During the performances, they and their audiences might escape for an hour or two into a happier world.

This stability of location and personnel allowed the POWs in the Wampo camps time to organise some credible camp entertainment. Fergus Anckorn (aka Wizardus) contributed to these small shows.

Almost burning to death

In around April 1943, when the Wampo viaduct scaffolding was complete, Anckorn was told to climb to the top and start coating one of the viaduct’s support pillars with a boiling-hot creosote.

But Anckorn couldn’t climb the pillar due to his bad leg. He was still using a rope to lift up his foot to help him walk. When he tried to indicate this to the Japanese guard, the guard “immediately went and got a bamboo pole to beat me up.” Given this additional inducement, Anckorn started climbing. It was a long way up. When he got to the top, he froze, suffering from vertigo; he couldn’t look down, he couldn’t let go off the scaffolding, he couldn’t even open his eyes. The engineer bellowed at him to start work, but he couldn’t move.

“And he came up after me. Took him about thirty seconds, up like a monkey, right? And he flung all the creosote over me. And I remember, I put my head [down] so none of it hit my face—I had this hat thing on. But the rest—it was all over me—and a hundred degrees. And I just started blistering everywhere: one huge blister. I looked awful. And pain too. I don’t know how I got myself down, but I did. And when I was near enough to the river, I flopped into the river.”

Fergus Anckorn’s injuries were so severe, doctors evacuated him to a convalescent camp at Chungkai, where he spent the next eight months of his captivity.

This example of Japanese brutality saved Anckorn’s life, for it took him away from the construction work. He found out later that all of his friends from his regiment who stayed on at Wampo, died before the month ended.

Starved of food and medicines and forced to work impossibly long hours in remote unhealthy locations, over 14,000 POWs died building the Thai-Burma railway. The number of rōmusha dead probably reached up to 94,000.

Read Part 1 and Part 3 of this blog article and look out for Part 4 to find out how Anckorn used magic to survive captivity.

For further information on Fergus Anckorn’s life in magic and wartime experiences, read Captivity, Slavery and Survival as a Far East POW: The Conjuror on the Kwai by Peter Fyans and Surviving by Magic by Monty Parkin. Also see, Captive Audiences / Captive Performers: Music and theatre as strategies for survival on the Thailand-Burma Railway 1942-1945 by Sears A. Eldredge.

*** AVAILABLE NOW ***

The Colditz Conjurer tells the amazing true story of Flight Lieutenant Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker, Battle of Britain pilot and prisoner-of-war magician.

Written by the Magic at War team, The Colditz Conjurer is a remarkable tale of perseverance, courage and cunning in the face of adversity. It features over 55 original photographs and maps. 126 pages.

Comments

Post a Comment