For Prisoners-of-War (POWs) of all theatres of war, entertainment in prison camps provided much needed enjoyment and escapism. During the performances, the entertainers and their audiences might escape for an hour or two into a happier world.

“I remember when we rehearsed and all that sort of thing, you quite forgot that you were in these terrible circumstances. We were learning a script and getting on with it, and doing our little show. Lots of laughs backstage, and that sort of thing... and it undoubtedly helped us along as well. In fact, there’s lots of performers survived the war when others didn’t.”

And, in a world where the POWs otherwise had no control over their lives, the ability to decide what to produce and then take that choice from its planning stage through to performance gave those involved an enormous sense of control, even if it was only momentary.

More than this, for POW-entertainers who endured years of neglect, malnutrition, disease, slave labour and death, working on theatrical productions and other forms of entertainment, aided in retaining their sense of identity and their humanity.

“As they told their jokes, sang their songs, and played their musical instruments - and audiences warmed to their efforts - their own tiredness fell away, their energy returned, and they, as well as their audiences, were enlivened and given the will to live a bit longer. For audiences, the experience of rapport prompted metaphysical speculations,” wrote Sears A. Eldredge in his detailed examination of music and theatre as strategies for survival for POWs working on the Thailand-Burma Railway, as captives of the Japanese.

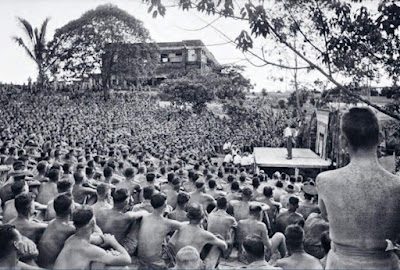

New Camp Theatre at Chungkai, Thailand (1944)

(Source: IWM - George Stanley Gimson)

These performers lifted the spirits of those who experienced their productions and helped them heal and survive. “By engaging an audience who needed something meaningful emotionally to hold on to, perhaps they temporarily sustained the will to live,” concluded Holocaust research, Rebecca Rovit.

As a niche performing art, magic played its role in the array of entertainments which boosted POW morale. Research shows that magic has a range of emotional, cognitive, and social benefits. Played for comic effect, for example, it helped release physical tension and stress in the prisoners. Like other entertainments, magic performances prompted memories of music halls and variety theatres; creating powerful emotional responses among prisoners who longed to be back home. A primarily visual art, magic had the added advantage over some other entertainments, in that tricks can be performed silently, or to music, which was useful for POW communities of mixed nationalities.

Perhaps more than any other entertainment, magic gave the prisoners hope and freedom. It is an art form about achieving the impossible. And while it could not produce physical freedom, it engendered a sense of mental freedom. Of being able to imagine what could be possible and to perceive a life beyond the wire. “My brain is the key which sets me free,” said American Hungarian escapologist Harry Houdini, an apt phrase for the POW’s circumstances.

The scale and quality of POW camp entertainments varied from simple campfire sing-a-longs and joke telling, to full-blown productions with costumes, orchestras, sets and special effects. In many settings, the camp authorities supported this activity, observing that the entertainments improved the POW’s morale, and potentially deterred them from escaping or causing the guards too much trouble.

Close-up magic

Examples of magic in POW camps included small scale, ad hoc performances, such as card tricks or sleight-of-hand performed one-on-one:

“‘Bush’… had a trick where he would hold a match upright on his sleeve and when he let it go, it used to jump a couple of feet in the air.,” said a fellow prisoner of Vince ‘Bush’ Parker, held in the infamous Colditz Castle.

Flight Lieutenant Vincent Parker and Oflag IVC (Colditz Castle) map

(Source: various)

Paul Potassy, an Austrian-born professional magician would often perform a small, improvised trick involving a dark bread called ‘khleb’ when he was a prisoner in Russia:

“I made three bread balls out of the bread, swallowed the bread balls, hit myself on the head and the bread balls came out and then disappeared again. I did the trick about six times per day and ate a lot of bread as a result.”

Paul Potassy in military uniform (1942)

(Source: 'Heroes of Magic' by John Fisher)

Parlour and stage acts

POW-magicians would also take to the stage - where there was one - as part of an ensemble production, like a revue or variety show. In the Far East, Fergus Anckorn joined a concert party and performed an act under the stage name ‘Wizardus.’

“At Ubon [a POW camp in Thailand] I borrowed a hat and after showing it empty produced from it three live kittens.”

Fergus Anckorn and a Changi POW camp theatre

(Source: Fergus Anckorn and Australian War Memorial)

Semi-professional Dutch magician Anton Hugo (known as ‘Dick’) Trouvat was another magician in the Far East:

Spotlight Review 1945 (Changi Goal)

(Source: Jack Wood Collection)

Australian

Sydney Piddington (later a post-war sensation with his wife Lesley in a two-person telepathy act) was another POW who performed magic while incarcerated by the Japanese. He was held in the Changi prison complex in Singapore and briefly joined a concert party as their resident magician.

A theatre programme made by POWs for Sweet and Hot, a variety show in one of the Changi camps. Sydney Piddington performed magic in the show under the billing ‘Mystery and Magic’

(Source: Jack Wood Collection)

Later, in 1944, with fellow prisoner Russell Brandon, Piddington developed the telepathy act which would later define his career. They were ‘a hit’ around the Changi peninsula and excited debate and conjecture among the other prisoners, about whether their mental feats were trickery or real.

A drawing of Sydney Piddington (at the chalkboard) and Russell Braddon (blindfolded) performing their telepathy ‘experiments’ in Changi, Singapore

(Source: Ronald Searle)

Amateur British magician Charles ‘Eric’ Ryder, imprisoned in Stalag VIII-B in modern-day Poland also entertained with a magic act, using an impressive array of improvised props:

“The Chinese Rings were constructed from wire purloined from the outside fence of the camp and the Dyeing Silks by procuring by devious methods a number of near silk handkerchiefs which were issue. He was able to construct an Inexhaustible Box from odd bits of timber and alarm clocks, which rested, from tines which once contained pudding and various other comestibles. A dressing gown cord, very ornate, was utilised for the silks from cord effect and used razor blades ground down were ideal for the Razor Blade effect. An old picture frame made a presentable card frame.”

British Army officer Wilfred Ponsonby was another conjurer in captivity. He performed regularly for his fellow POWs while a prisoner in Spangenberg Castle in Germany and in the other camps where the German authorities held him. Ponsonby got hold of props for his acts by writing to his wife and asking her to send them over in the post:

On 23 November 1940, he wrote, “I would... like one or two conjuring props, thumb tips for paper tearing & cigarette trick, etc.”

A few months later, on 28 April 1941, he added, “I would like some conjuring gadgets. Send these in my personal parcel not from a shop. The Sympathetic Silks i.e. 3 pairs of silks (one pair heavy silk, the pink pair if you can find them & two pairs thin jap. silk contrasting colours – you will have to make these up.) They should be a yard square; one box elastic bands, Anchor brand No. 8. Also, hank for rope trick. They are in my uniform case at Fleet. Thumb tips,”

Wilfred Ponsonby

(Source: 'Quicksilver', Wilfred Ponsonby)

Besides performing their own magic acts, magicians in the camps would join in with other acts and productions, such as playing a straight man to a comedian, or joining in with all-cast singing or dancing spots. Or they performed a second act. For example, Charles Ryder developed a ventriloquist act and Anton Trouvat performed hypnotism.

Pantomimes

There was also an obvious role for a magician during pantomime season, where their magic could be easily woven into the (often thin) plot.

Cricketer and part-time magician, Bill Bowes, filled this role when he was in Oflag-79 in Germany:

“Bowes always took a leading part in camp activities... Perhaps his biggest stage success was in the part of a magician in the pantomime 'Aladdin,' which gave full rein to his considerable talents as a conjuror.”

Read more about

Bill Bowes here. Charles Ryder also did a stint as the magician in Aladdin while he was a POW.

W. E. (Bill) Bowes, conjurer

(Source: Bowes, W. E., Express Deliveries (1950))

And,

Sydney Piddington, held by the Japanese in Singapore, appeared in the pantomime,

Cinderella, as a magician.

A theatre programme for the pantomime Cinderella, featuring Sydney Piddington as the ‘Magician’

(Source: Jack Wood Collection)

Lectures

Aside from theatrical productions, POW camps had active lecture circuits. Prisoners went from hut to hut to lecture on topics they had some knowledge about. Fergus Anckorn gave a lecture on Houdini's life. Professional English magician Lincoln Lee (real name Leslie Matthews) lectured on the history of magic and on famous magicians while he was in Stalag Luft VI (in modern day Lithuania). In doing this, “he found a ready audience.”

Sgt. Leslie Matthews RAF (aka Lincoln Lee)

(Source: The National Archives, UK)

Full shows

Exceptionally, a magician would put together an entire show. This required a significant amount of material and props. Unsurprisingly, in the two examples below, both performers were professional magicians before the war.

Ludwig Hanemann, a German magician in a Welsh POW camp, performed regularly for his fellow prisoners and developed a sell-out camp variety show called Simlalabim, in a nod to Dante’s catch-phrase Sim Sala Bim. Appearing under the stage name, Punx, he performed manipulation, general magic, mentalism and even homemade illusions.

“I put together some two-hour shows with professional lighting and music. I even had real posters painted. Admission was one penny.”

Punx (Ludwig Hanemann) POW camp show poster and pre-war photograph

(Source: Ludwig Hanemann)

Read more about Punx here.

On the other side of the world, before the Japanese sent him ‘up country’ to work on the Thai-Burma Railway, Cortini (real name Johan Hubert Crutzen) also did a full-stage show. In January 1943, he put on Magic Nights in a space known as The Palladium Theatre in the POW complex in the Changi peninsula of Singapore. Fergus Anckorn did a spot in the show and recalled:

“As the theatre’s facilities were so good, we’d put on full magic shows, with the Professor’s illusion act – sawing people in half and things like that – and me doing a limited amount of conjuring.”

“One show we did started in a macabre tone in keeping with our surroundings. The lights would go down and the curtains would be partially opened with the Professor standing there between them. But, as you looked, he would gradually turn into a skeleton – a complete skeleton – and then he’d turn back into a man again, bow and disappear behind the closing curtains.”

Other illusions included a guillotine, a suspension and possibly one involving live animals.

A programme for the Magic Nights,

starring The Great Cortini with Fergus Anckorn (January 1943)

(Source: The Jack Wood Collection)

POW magic beyond the wire

Occasionally, the POWs also entertained local communities, sharing the enjoyment of magic beyond the wire. Punx gave magic shows for local children in the community near his POW camp in Wales. An unknown Italian POW-magician did the same in Bedfordshire in the East of England. In the BBC WW2 People’s War archive, John Hughes recalls growing up in wartime neat to No. 72 (Ducks Cross) POW Camp. He remembered that “every Christmas they used to come up to the school and pick us up in this canvas topped lorry, we used to scramble in the back and they used to take us down for a Christmas party that they used to lay on for us, the Italians.” The party would normally consist of a meal, a magic show and music from the camp orchestra.

No. 72 (Ducks Cross) POW Camp, Colmworth, Bedfordshire, England

(Source: repatriatedlandscape.org)

*** AVAILABLE NOW ***

The Colditz Conjurer tells the amazing true story of Flight Lieutenant Vincent ‘Bush’ Parker, Battle of Britain pilot and prisoner-of-war magician.

Written by the Magic at War team, The Colditz Conjurer is a remarkable tale of perseverance, courage and cunning in the face of adversity. It features over 55 original photographs and maps. 126 pages.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment